Help, my horse has laminitis!

Your horse’s hooves are unusually warm, the pulse at his fetlock is throbbing, and pain is making him take on a sawhorse-like stance. You’re fairly sure it’s laminitis. What now?Call your vet

Suspected laminitis is always an emergency that warrants the swiftest possible veterinary care. If you horse is actually suffering from acute laminitis, the first 48–72 hours of treatment are critical. If you can get the inflammation under control during this time, the damage to the hoof’s suspensory apparatus can be contained and the horse can get back to its old self more quickly.

Before the vet arrives, there are some early measures you should take to give your horse some relief. Make sure your horse has a soft surface to stand on in the barn. Thick shavings, sand, or peat are all suitable options. Keep other horses close enough to be seen, but not so close that they impede the affected horse’s ability to quietly stand or lie down. Don’t let them out with the herd!

Another thing you can do is cool off his feet with crushed ice or even frozen peas in disposable gloves or freezer bags. Apply them to the coronary bands of all four hooves, with a layer of cloth between them and the hooves. Ask your vet when you should stop cooling prior to their arrival so that they can accurately assess the warmth of the hoof capsule and the pulsation.

The vet will also carry out other examinations such as pressing on the sole and x-raying the hoof capsules. In acute stages the x-rays will show no observable changes if there is no earlier damage – nevertheless it’s important to establish a baseline for assessing the disease’s progress in later x-rays. The vet will also try to find the cause.

Laminitis is commonly triggered by feed

There are several factors that can cause laminitis. In most cases, however, it is connected with an imbalance in insulin metabolism. Affected horses have an insulin resistance and/or insulin dysregulation, which causes abnormally high insulin levels in the blood and has far-reaching consequences for metabolism.

- Overweight horses are often affected because fat tissue lowers insulin sensitivity in cells (equine metabolic syndrome, EMS)

- “Thrifty” breeds are often genetically predisposed to insulin resistance because they have been bred to need very little feed – some even have the typical metabolic condition for EMS with insulin resistance, with increased risk of laminitis, at normal weights

- Horses with

- often develop insulin resistance consequent to the disease

However, there are other triggers besides metabolism-related laminitis:

- A one-time overfeeding of easily fermentable carbohydrates (like starches or fructans) can also lead to laminitis: when large amounts of these compounds land in the large intestine, they create an imbalance in the bacteria that dwell there, with a proliferation of lactic acid-forming microorganisms in particular, and other organisms dying off in large numbers. These dying bacteria release endotoxins, resulting in damage to the intestinal wall through the swift increase of lactic acid in the gut. The endotoxins enter the bloodstream and trigger a circulatory disorder in the dermis.

- Bad cases of colic can also lead to endotoxins being released in the gut and entering the bloodstream

- Endotoxins from the uterus can enter the blood after a mare gives birth

- An oversupply of selenium can also cause a serious case of laminitis (selenium poisoning)

- Laminitis can be caused by an overdose of certain medications

- Concussive (or traumatic) laminitis from riding on hard surfaces over very long distances is quite rare today. Concussive laminitis in individual legs may occur when the horse compensates for a lame leg, causing chronic, severe lameness in the opposite limb.

With laminitis, consistent treatment is key

Laminitis is a serious matter. It is one of the most painful diseases a horse can have and leads to severe, chronic problems if insufficiently treated. Long-term management is essential in addition to prompt treatment of acute episodes, especially in the case of the oft-seen metabolic laminitis. A treatment plan developed by your vet is therefore essential.

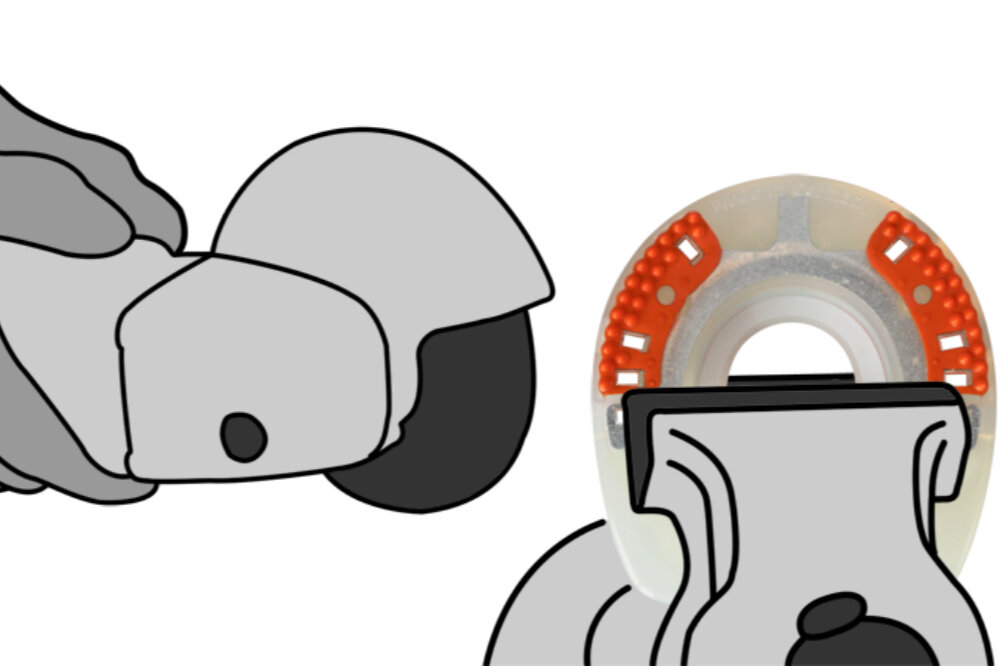

The vet will prescribe medication, along with consistent cooling over a minimum of two to three days and soft standing surfaces in the stable. For horses with Cushing’s syndrome, it is important that the underlying disease be treated promptly. If necessary, the hoof should also be protected to counteract rotation of the coffin bone in the hoof capsule. There are many varieties of hoof protection, and not every horse will feel immediate relief from it.

After the inflammation has subsided, your vet and farrier will decide together which hoof protection is most appropriate during the healing phase with the help of x-rays taken during the healing process. The horse should initially be given some form of hoof protection after contracting the disease, even if it is accustomed to being unshod. Depending on the horse, complete recovery of the hoof capsule may take up to twelve months, during which there must be no further inflammation. The hooves are still weak during this time, so always follow your vet’s prescribed exercise programme after your horse’s recovery from laminitis.

Proper diet at all costs

Whatever the cause, horses with acute laminitis should be given only hay, supplemented with straw if needed. Feed plays a major role in metabolic laminitis, even after the inflammation has subsided. Avoid fluctuations in blood sugar in horses with insulin resistance. Overweight horses must slim down – and since exercise isn’t possible in the early stages of recovery, this means that a strict diet is in order.

For an easy doer that’s not in work to lose weight, the hay ration must be reduced to below 1.5 kg per 100 kg of target body weight. This quantity covers the daily energy requirement, meaning that a horse must receive less energy than that in order to lose weight. A hay-straw mix will allow the horse to satisfy his natural need to chew. This means that the 1.5 kg of forage per 100 kg may consist of up to one third straw. Because straw contains less energy than hay does, it will create a slight energy deficit. Once a week, measure your horse’s girth with a measuring tape to see whether the diet is working: the horse’s circumference measurement should be approx. 1–2 cm smaller each week.

To lose body fat but retain muscle tone, it can make sense to supplement your horse’s feeds with amino acids, depending on the hay’s nutrient content. You should also give your dieting horse a mineral feed to ensure that he gets enough minerals and vitamins.

A horse that was formerly overweight and laminitic but now at an ideal weight cannot be fed as if he were never ill. Continue to avoid feeds that are high in easily digestible carbohydrates, such as cereal starches. Because, as mentioned above, insulin resistance can also affect horses at normal weights. This means that insulin peaks in the blood still pose a risk of the laminitis returning. If your laminitis-prone horse needs concentrates for hard work and hay alone isn’t enough, feed him alternative energy sources like low-carbohydrate, cereal-free concentrates and oils.

Laminitis and turnout – a complicated subject

Turnout is naturally taboo for acute cases of laminitis. Overweight horses that had laminitis in the past should also not be turned out. This is because the nutrients in the grass can vary greatly depending on weather, pasture maintenance, and species diversity. During periods of cold nights under 10 degrees Celsius together with sunny days, the fructan content of pasture grass can be quite high. Such grass is especially tasty and some horses will therefore eat lots of it, which can lead to high insulin peaks in the blood and which is why grazing during this time can pose a risk of recurrence.But what about a formerly laminitic horse that is slim and in training? Exercise caution here, too, because when the horse eats large amounts of high-fructan grass, this can result in dangerously high insulin levels. Turnout should therefore be limited – for example in a fenced-off area and with the horse wearing a well-fitting grazing muzzle that won’t damage the teeth.

Some important points about grazing and laminitis:

- Even a one-time, accidental “overdose” on delicious pasture grass can be risky for laminitis-prone horses. Pasture fences must be escape-proof, and everyone who turns out horses must be informed whether (and under what precautions) a laminitis-prone horse may be turned out.

- Horses turned out for shorter periods of time will often eat faster and consume just as much grass as if they’d been turned out all day. This means that limiting turnout time alone will not make grazing safer for horses prone to laminitis, as time restrictions by themselves often will not sufficiently limit grass intake! Regulate and slow down grass intake through the use of a grazing muzzle, if possible.

- While shorter grass is known to be high in fructans, don’t assume that long grass is always low in nutrients. Even over-mature grass can be dangerous: horses often seek out high-energy grass seeds, which are comparable to concentrates.

Food as the language of love: can I still give my horse treats?

We all love to feed our four-legged sports and leisure partners. Every rider wants to be able to offer a treat here and there, and rare is the horse that will say no to a tasty reward from your hand or his feed trough. If your horse has laminitis, it can be hard to resist the urge to feed him extra treats, especially if he’s on a strict weight loss diet. Horses in this situation are often quite frustrated and seem hungry.

But every extra in the ration means more calories that can have a negative effect on the disease and increase the risk of recurrence. Avoid all unnecessary additions in the form of treats, mash, muesli, bread, or fruit, even if the product is touted as “low energy” or “diet feed”! All feeds contain energy (calories).

If you absolutely must give your horse a reward, here’s one thing that would be acceptable: one single (!) fresh carrot per day. Contrary to their reputation, carrots are neither especially high in sugar nor in energy. Of course they contain some, which is why you should limit them to one per day.

Chronic laminitis: painful and preventable!

If the laminitis becomes chronic due to faulty management and diet, the position of the coffin bone changes in the hoof capsule. It may both rotate and sink downwards. Repeated pressure from below due to the changed position can also cause deformation of the tip of the coffin bone, forming a protrusion (sometimes called a “ski tip”).

These changes can be seen in x-rays and the severity can be assessed by marking certain points on the hoof capsule with radiopaque markers before the x-rays are taken. These markings are important so that the vet can make a prognosis for further treatment. The penetration of the coffin bone through the sole is a serious complication of chronic laminitis.

Chronic laminitis can often be detected with the naked eye: the dorsal hoof wall becomes concave and displays one or more “founder rings”: horizontal rings sloping towards the heels, showing an uneven growth of the horn. Afflicted horses often must deal with recurrent hoof abscesses, as the lamellar layer is no longer intact. They also display a typical “pottery” gait (landing heel first) in an attempt to avoid putting weight on the painful toes.

In fact, chronic laminitis is not always clearly recognisable. There are many overweight horses that never show signs of acute laminitis. Rather, there are small signs you should look for: Affected horses always move somewhat gingerly. They seek soft surfaces in the paddock and may lie down more often than others in their herd. The white line is slightly wider near the toe, and perhaps the farrier is having a difficult time keeping the toe sufficiently short. All these can be indications of inflammatory processes in the hoof capsule and should not be overlooked, as changes in the position and shape of the coffin bone may also be occurring.

The good news is that, if your horse is given good and conscientious care, it doesn't have to come to that. Prompt and consistent treatment can ensure that the horse’s hooves are not permanently damaged. The only thing that remains – the increased, permanent risk of recurrence – can be kept quite low through optimised management, feeding, and work.

Horses with laminitis should be fed low-carbohydrate feed rations to avoid high insulin secretion. This can be done by eliminating cereals (including products containing rice) from the ration. Hay that is high in sugar can be soaked in water to flush out the water-soluble sugars. It is important that the hay not be simply made wet, but that it be thoroughly washed over a period lasting at least 30, ideally 60 minutes. Overweight horses must lose weight so that they do not contract laminitis again. Here, it is recommended that the horse's daily hay ration be weighed.

The horse's mineral feed should contain more than the required zinc and vitamin E. To ensure the supply of all vital micronutrients, we recommend supplementing our Seniormineral, which contains essential amino acids as well as more zinc and vitamin E.

Underweight laminitis horses (for example those with Cushing's) will benefit from oil (such as OMEGA3 Pur) as a sure source of energy that's carbohydrate-free.

November 2021, © AGROBS GmbH

Sources:

- Coenen, M.; Vervuert I.: Pferdefütterung. Georg Thieme Verlag KG, Stuttgart, 2020

- Gesellschaft für Pferdemedizin: Hufrehe-Leitfaden (2017). Zur Sorgfalt bei der Diagnostik und Therapie der Hufrehe.

- Kienzle, E., Fritz, J: Fütterungsbedingte Rehe – Rezidivprophylaxe beim übergewichtigen Pferd. Tierärztliche Praxis Großtiere 4/2013, S. 257-264

German

German French

French

-for-horses.jpg)